A new study highlights flaws in stories that conservation organizations often tell about how protected areas can improve the wellbeing of local people. It shows that some of the most entrenched narratives lack evidence and need more nuance. But it found stronger evidence for narratives that centre the rights and roles of indigenous people and local communities.

The findings are timely as the global community is striving to agree a new plan for conserving the planet’s biodiversity and securing the benefits it provides us. That deal, set to be agreed at the 15th Conference of Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity in December 2022, could include a target of increasing protected areas to 30% of the world’s land area, from about 17% today.

The target has the backing of more than 100 countries and some major conservation organizations. But groups focusing on human rights, such as Survival International, Amnesty and the Rainforest Foundation UK say it is a “disaster” waiting to happen.

“Should it go ahead, it will constitute the biggest land grab in history, and rob millions of people of their livelihoods,” said Fiore Longo of Survival International in a press release on 1 December. “If governments are really meaningful about protecting biodiversity, the answer is simple: recognize the land rights of Indigenous peoples.”

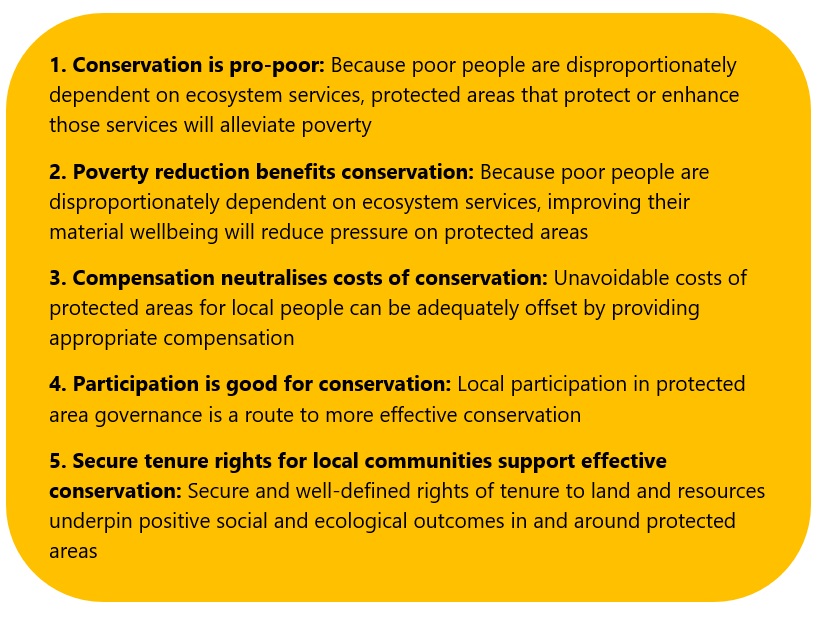

The new study on conservation narratives, in the journal UCL Open: Environment, lends weight to that argument. The researchers investigated evidence for each of five common narratives about protected areas and human wellbeing in countries that the World Bank defines as low- or lower middle-income.

These narratives are prevalent. One or more of them appears on 138 of the 169 websites of conservation organizations that the study team reviewed. More than 70 percent of these organizations used the “conservation is pro-poor” narrative.

“We see these narratives or stories playing out and being very powerful in directing conservation interventions,” says lead author Emily Woodhouse, an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at University College London. “These stories and narratives have value. They help organisations be efficient to roll out particular types of program or project. But the problem is if they override complexity. Using them in an unthinking way can be quite dangerous.”

Woodhouse told me that the first three narratives are particularly problematic, especially if they are used, “in a simplistic way that doesn’t account, for example, for broader ideas of wellbeing and only looks at material poverty”.

For example, compensation for the lack of access to natural resources, or for damage caused by wildlife to crops, is rarely sufficient. And it often fails to compensate for cultural losses alongside economic or material ones.

Similarly, while protected areas or ecotourism projects conservation can benefit poor people living nearby, they can also significantly harm them if they exclude them from accessing and using local natural resources.

“There is evidence that material poverty can decline with those kinds of projects,” says Woodhouse. “But there are also much wider issues around justice and broader wellbeing, and the fact that the poorest often lose out in these kinds of projects. What’s at stake is social justice.”

The other two narratives were better supported by the evidence the study team assessed. But the best-supported narrative — that secure tenure rights for local communities supports conservation — was also the least prevalent on the websites of conservation organizations, appearing on less than a quarter of them. Woodhouse says this is likely because the conservation sector is still catching up with the development sector about the importance of tenure.

“The emphasis on land tenure is relatively new,” says Woodhouse. “It has come alongside recognition that indigenous and local communities manage something like a quarter of all land across the world.”

These communities protect about 80 percent of the world’s biodiversity on that land. And there is growing evidence that they tend to manage land and resources better than state actors do. In 2021 for example, a review of evidence published in the journal Ecology and Society showed that conservation initiatives that centre indigenous people and other local communities tend to be more effective and fairer.

Lead author Neil Dawson of the University of East Anglia, and colleagues, looked at 169 studies and concluded that empowering and supporting the “the environmental stewardship of indigenous peoples and local communities represents the primary pathway to effective long-term conservation of biodiversity, particularly when upheld in wider law and policy”.

The study by Woodhouse and colleagues comes as countries are negotiating a new Global Biodiversity Framework — a 10-year strategy for addressing the biodiversity crisis. With time short, there is an urgent need to ensure that conservation solutions bring both social and ecological gains. But there is a risk that entrenched narratives will get in the way of the best outcomes.

Woodhouse says the draft Global Biodiversity Framework text “ticks all the boxes” by mentioning justice, equity, participation, and indigenous people and local communities, but says there are issues with nuance.

“There’s an emphasis on local communities as ‘stakeholders’, rather than being agents of change,” she says. “The emphasis should be shifted. And that goes for women as well, and marginalised groups.”

How the Global Biodiversity Framework is implemented within countries “is going to be really important, for justice and also the success of conservation,” she says. “It is about the most marginalised people losing out from these processes and the importance of putting local people and indigenous communities at the centre, for their voices to be heard and for governance structures to embed local systems and local knowledge into them.”

References:

Woodhouse, E. et al. 2021. Rethinking entrenched narratives about protected areas and human wellbeing in the Global South. UCL Open: Environment 4: DOI: 10.14324/111.444/ucloe.000050

Dawson, N. M. et al. 2021. The role of Indigenous peoples and local communities in effective and equitable conservation. Ecology and Society, 26: 19 https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12625-260319

Photo credit: The Jenu Kuruba hold signs at their protest outside Nagarhole National Park in India, where they are being evicted in the name of conservation. © Survival International

Related posts:

Explainer: COP15, the biggest biodiversity conference in a decade

Will 30×30 reboot conservation or entrench old problems?

Human wellbeing threatened by ‘unprecedented’ rate of biodiversity loss