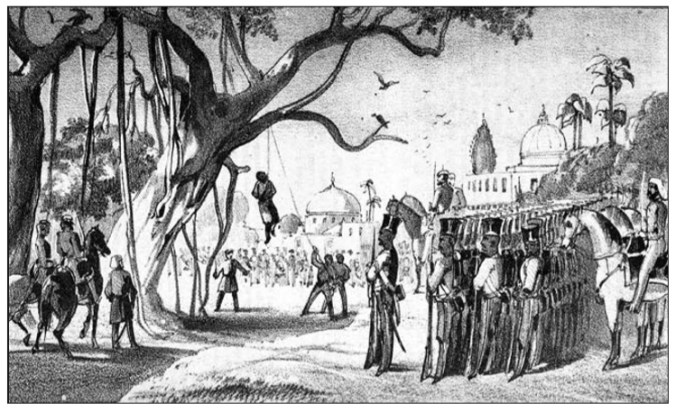

Public execution of an Indian rebel in 1857

When British soldiers hanged Indian rebel Amar Shahid Bandhu Singh from a sacred fig tree in 1857, a legend was born. Local stories say the execution took seven attempts and that, when eventually Singh died, the tree began to bleed.

The public hanging took place in Gorakhpur in what is now the state of Uttar Pradesh. The tree — at which Bandhu Singh had worshipped the goddess Durga — was just one of many sacred fig trees the British used as gallows during their control of the subcontinent.

Many hundreds and perhaps thousands of local people died hanging from these trees — most commonly banyans (Ficus benghalensis) but also peepal trees (Ficus religiosa). Both are species of strangler figs that have played important roles in the culture and religion of the region for thousands of years. Both are sacred to people of diverse faiths, especially Hindus, Buddhists and Jains. They are abodes of gods, and symbols of life, fertility and knowledge.

Yet repeatedly — see list below — the British turned to these trees as gallows. In 1860, in Bareilly in Uttar Pradesh, they are said to have hanged 257 rebels from the branches of an individual banyan in a single day. These public executions were designed to not only punish but also to terrorise the local populace.

A British soldier, Sergeant William Forbes-Mitchell, published an account of what happened when colonial forces captured “great numbers” of local men in another part of Uttar Pradesh. “I cannot say what form of trial the prisoners underwent, or what evidence was recorded against them,” he wrote.

“I merely know they were marched up in batches and shortly after marched back again to a large tree of the banyan species which stood in the centre of the square — and hung thereon. This went on from about 3 o’clock in the evening till day-light the following morning when it was reported that there was no more room on the tree, and by that time there were one hundred and thirty men hanging from its branches. A grim spectacle indeed.”

“Locals were forced to watch these executions,” says Kim Wagner, a senior lecturer in British imperial history at Queen Mary, University of London, and the use of sacred trees “surely exacerbated the horror felt”.

While no historical evidence suggests the British chose fig trees as gallows because of their religious significance, they would surely have known how important these trees were to local people. British writing from the colonial period abounds with descriptions of people praying at and revering banyan and peepal trees.

The hangings fit into a pattern of what Wagner has called the “racial arrogance and callous brutality” of the British empire, and the “colonial ritual of violence during the nineteenth century”.

The banyan from which Sangolli Rayanna was hanged in 1831

The executions were cruel spectacles. In 1857, after they hanged 144 rebels from the branches of a huge banyan in Kanpur, the British threw the corpses into the River Ganges. Other times, they prevented families of those executed from taking the bodies away. Instead the bodies remained, decomposing in full public view.

Gajendra Singh, a lecturer in South Asian history at the University of Exeter, points out that such treatment of a body after death precluded traditional funeral rites from taking place. “The rotting corpse not only pollutes the environment in a physical and religious sense, but is something beyond religious rites of cremation or burial,” he told me.

In a 2016 paper, Wagner wrote that: “Colonial violence ultimately undermined colonial rule by alienating the native population and turning its victims into martyrs of nationalist movements.”

After India gained its independence in 1947, it adopted the banyan as its national tree. Since then, memorials have been installed at several of the fig trees. Some of the trees are still alive today, but others have fallen and are passing out of collective memory.

On 25 May 2010, The Times of India reported that an ancient hanging banyan in Kanpur had died of neglect. A stone inscription placed beneath the tree in 1992 had quoted the banyan itself at length.

“… No flower garlands are hung on my branches. Today thick bushes have grown around me and I am overrun with weeds. Everything is still and quiet and there is an aura of sorrow surrounding me. But even today I can hear the sounds of horses galloping, the screams of revolutionaries and the firing of canons. I am an old banyan tree, relegated to the margins of history… When I remember the cruelty of the British while punishing the revolutionaries I still get shivers up my spine.”

Related posts:

Why one fig tree in the middle of nowhere has a 24-hour armed guard

The majesty and mystery of India’s sacred banyan trees

Read more: My book Gods, Wasps and Stranglers tells the story of how fig trees have shaped our world and influenced our species over millions of years thanks to their curious biology. It explains how fig trees became rooted in the religions and culture of South Asia (as in many other places) and how these trees can help us to address big challenges in the 21st century.

Picture credits: Top: From Thomas Frost (1858) Complete Narrative of the Mutiny in India. Bottom: Praveenkumar112 (Wikimedia Commons)

Partial list of executions that used sacred fig trees:

1785 — Bhagalpur (Bihar): On 13 January, the British hanged rebel Tilka Manjhi from a banyan tree, after first tying him to the tail of a horse, which dragged him to the site of his death.

1806 — Medinipur (Odisha): On 6 December, the British executed Jayee Rajguru, who had led a local rebellion. They are reported to have tied Rajguru’s legs to two of a banyan’s branches and then pulled them part, splitting his body into two.

1831 — Kasaba Nandagad (Karnataka): On 26 January, rebel Sangolli Rayanna was hanged from a banyan.

1832 — Pune (Maharashtra): On 3 February, the British hanged rebel leader Umaji Naik from a peepal (Ficus religiosa) tree. A sign there says: “His dead body was hanged on this peepal tree for three days to strike terror into the hearts of the public.”

1857 — Barrackpore (West Bengal): Mangal Pandey, who fired the famous first shot of the 1857 War of Independence was hanged from a banyan tree on 8 April.

1857 — Gorakhpur (Uttar Pradesh): On 12 August, Amar Shahid Bandhu Singh was hanged from a sacred peepal tree. He was one of hundreds of freedom fighters said to have been hanged from the same tree.

1857 — Bijraul, (Uttar Pradesh): 26 men led by Shah Mal were hanged on a banyan

1857 — Satara (Maharashtra): Some of the leaders of an uprising were hanged from a banyan.

1857 — Sunehra (Uttar Pradesh): On 28 December, Baksha Singh was hanged from a banyan he had himself planted. Locals say nearly 200 people were hanged from the same tree.

1857 — Dhaka (present day Bangladesh): Hundreds were hanged from banyans in what is now Bahadur Shah park.

1857 — Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh: The British hanged 144 rebels from the branches of a single banyan, known locally as the Boodha Bargad.

1858 — Shamsabad (Uttar Pradesh): 130 men were hanged from a single banyan.

1860 — Bareilly (Uttar Pradesh): On 20 March, either 257 or 244 men were hanged from a banyan. The state government built a memorial tower next to the tree in 2006.

1871, Ludhiana, Punjab: On 26 November, Giani Rattan Singh and Sant Rattan Singh were hanged from a banyan tree for closing down slaughterhouses opened by the British.

References:

Agarwal, P. 2015. Municipal Corporation to light up memorial of 257 freedom fighters. The Times of India. 16 February 2015. [Read online]

Bageshree S. 2015. Banyan tree testimony to Rayanna’s hanging. The Hindu. 20 July 2015. [Read online]

CSAS. 2008. Mutiny at the Margins. Part 3. The Impact of the Mutiny. School of History and Classics. Edinburgh University. [Read online]

Financial Express. 2007. Accidental hero or a forgotten martyr. Financial Express. 8 April 2007. [Read online]

Forbes-Mitchell, W. 1893. Reminiscences of the Great Mutiny 1857-59. [Read online]

Ghai, A. 2009. Standing tall in memory of freedom fighters. Tribune News Service. 4 July 2009. [Read online]

Government of India. 1973. Who’s Who of Indian Martyrs. Volume 3. [Read online]

Hebbar, P. 2013. The Forgotten Freedom Fighter. The Indian Express. 7 April 2013. [Read online]

Kolhatkar, A. 2009. Satara’s Hanging Banyan Tree. Dadi Nani Foundation. [Read online]

Kumar, R. 2016. Photo Feature: Tilka Manjhi (11 February 1750 – 13 January 1785). Forward Press. 1 February 2016. [Read online]

Kumar, S. 2017. Indian mutiny: Remembering farmers who fought British rule. BBC News. 12 July 2017. [Read online]

Mishral, I. 2012. Boodha Bargad dead, but its tale still alive. The Times of India. 9 August 2012. [Read online]

Rout, H.K. 2012. Villages fight over martyr’s death place. New Indian Express. 6 December 2012. [Read online]

TNN. 2016. 250-yr-old tree that stands as a testimony to British atrocities. The Times of India. 14 August 2016. [Read online]

Tribune News Service. 2000. The tree on which two Namdharis attained martyrdom. Tribune India. 12 June 2000. [Read online]

Vigi, S. 2010. Apathy kills Boorha Bargad. The Times of India. 24 May 2010. [Read online]

Wagner, K.A. 2016. ‘Calculated to Strike Terror’: The Amritsar Massacre and the Spectacle of Colonial Violence. Past & Present 233: 185–225. [Read online]

Willcock, S. 2015. Aesthetic Bodies: Posing on Sites of Violence in India, 1857–1900. History of Photography 39: [Read online]

Hi Mike,

When is your new book audio book version available. I live near a very big banyan tree. I hope you can tell me how old it is. Here is a picture. It Is located in the Normandy Shores Golf course in Miami Beach Florida 33141. I became intrigued by old trees when after I watched a video on youtube that made it very clear just about all old growth trees are gone. Vanished forever. And when you do happen to see one, appreciate it for what it is. And what it is, is a lot more than I can comprehend. I sometimes visit this tree and use the vines to climb up it. Use the vines as ropes sort of. One day, The sun was coming down and the most beautiful red sunlight was shooting through the tree. I was up in the top of it and connected with that tree at that moment on some other not so human plane. I imagined that this tree would make a home to people in the much distant past. It felt very natural and organic to be up in that tree. It is that big and solid. And this tree of course. Is tiny compared to what used to live, I don’t know so many thousands of years ago. Correct me if I am wrong but it is not inconceivable that 10,000 years ago or maybe more, a tree like this would grow to 10 times the size it is now or maybe more. Is there evidence of this. And if it were something that big, it could for sure serve as a secure home. I love your work!

[cid:image001.png@01D3D25D.01E9FE20]

[cid:image012.png@01D3D264.70889C40]

[cid:image007.png@01D3D264.70CC34F0]

Hi David

Thanks for dropping by, and for reading my blog post. The audiobook is available now from Audible.com, under the US title Gods, Wasps and Stranglers. Unfortunately your photos didn’t arrive so I can’t comment on the banyan, but you’re right to say they grow into unfathomably large specimens. There is one in India that is big enough for 20,000 people to stand beneath its crown (see this post). I’m sure people used to make their homes in these trees many thousands of years ago. They have served as cyclone shelters too (see this post). There are some great photos of a giant banyan here too: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/great-banyan-tree. I like how you described that connection you felt with the tree. Keep on climbing!

Hi Mike,

This is a great piece of work. Few days back I was reading an article about Indian hill stations of colonial period. Indigenous spaces, flora, fauna were destroyed and replaced by foreign trees in those regions, which was a kind of violence. As you mentioned British choose banyan and peepul trees for the execution, was there any specific behind this ?

Thanks! It may be that the British chose these trees because they were common and, in the case of the banyans, large enough for multiple hangings. You might also be interested in this post about how fig trees in Kenya https://underthebanyan.blog/2018/04/11/when-happened-when-christian-missionaries-met-kenyas-sacred-fig-trees/

Don’t you think there were attempts by British authority to interfere into Indian social life, because these trees were regarded as ‘pious’ by many people. Initially, British also tried to control and imposed its authority in every sphere. However, later with Queen Victoria’s proclamation ( 1858) they decided to not interfere into religious practices of native people. As I went through your article, most of the executions were during or before 1857. So, I was thinking, probably by choosing these trees they were trying to influence the social and religious life of native people.

Hi Colleen, I asked the experts I quoted above whether the British specifically targeted the fig trees because of their religious significance. Neither of them knew of any evidence to suggest this. In Uganda, though, forty years after Victoria’s proclamation (and while she was still on the throne), the British colonial administration bannned traditional religion. This had an important effect of culturally-important fig trees there. I’m writing about this now and will share the link soon. In India, most of the executions I mentioned were in 1857 because this was the year of a major uprising.

Hello again – here is the story about fig trees in Uganda https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/what-is-barkcloth-uganda

Informative, wonderful post thnx to share this lovely post