“Banditry, robberies, infiltration of small arms, poaching in the region’s game reserves and national parks and frequent outbreak of livestock diseases are now being attributed to the uncontrolled movement of pastoralists and their animals.”

This sentence, from a 2006 article in Kenya’s The Nation newspaper, encapsulates the way the country’s nomadic herders have been — and continue to be — portrayed in the media there. It echoes the dominant policy narrative, which says pastoralism is a backward system that takes place a harsh, unproductive environment and that when herders move to seek water and pasture they create problems for other people.

But this, say researchers, is a dangerous narrative, one that is blind to the true nature of the lands the pastoralists move across and to the knowledge they draw upon to take advantage of resources that are distributed there in an unpredictable way.

Today, the meat and milk pastoralists provide help to feed a nation. As the climate grows more variable, these people could become even more important cornerstones of Kenya’s economy and food security.

But, in the pages of newspapers there, the herders are not heroes — they are harbingers of conflict and other problems. In short, Kenya’s pastoralists have an image problem. This much became clear when I analysed 100 stories about pastoralists that Kenyan newspapers published between 2000 and 2012.

My study, which will also examine articles from India and China, is part of a larger Ford Foundation funded project. It aims to promote more progressive narratives, and policies that support mobile pastoralism as a rational, productive livelihood in lands where water and vegetation vary in space and time. Some patterns soon emerged:

- In Kenya, pastoralists tend to feature only in ‘bad-news’ stories – 93% of the media reports referred to conflict or drought.

- While 51% of stories that mention conflict presented pastoralists as a cause of problems, only 5.7% suggested that pastoralists might be the victims of the actions (or inactions) of others (e.g. farmers or government policies).

- An astonishing 22% of all articles referred to pastoralists as “invaders” or as having “invaded” land.

- Pastoralists have little voice. They were quoted in only 41% of the stories journalists wrote about them.

I supplemented my content analysis with an online survey that 42 Kenyan journalists completed. “The media only gives special attention to pastoralists when there is a crisis, like a major drought or famine where large numbers of people and animals have died,” said one. Another said: “Pastoralism is generally ignored. It only makes headlines when there is cattle-rustling and scores of people are killed.”

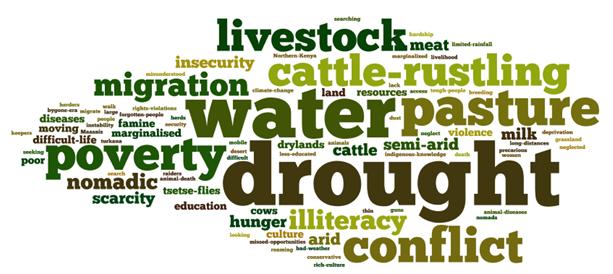

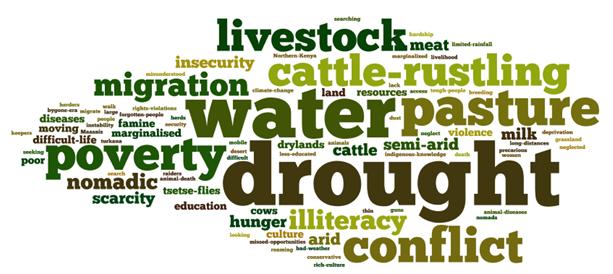

I asked the journalists to state five words they associated with pastoralists. The figure below shows the words they chose, with word-size reflecting how often a journalist used it.

It’s a problematic portrait. Yet when asked more specific questions, the journalists revealed knowledge and opinions that seem to contradict the dominant media narrative.

Most (91 per cent) of the journalists acknowledge, for instance, the importance of pastoralism to Kenya’s economy, with more than half of them stating that this is major. This surprised me, given that this was invisible in the stories I analysed. Only 4 per cent of them mentioned it, and not one published a figure such as a shilling, dollar or GDP value.

Other things the journalists said suggest that there is an opportunity for a new narrative to emerge in the Kenyan media, one that does not ignore the social, economic and environmental benefits pastoralists provide.

“The media has neglected pastoralism, since its takes place in far flung areas of northern Kenya which the government has neglected for years,” said one journalist. Another noted that: “Pastoralism has a chance to become a key growth sector for Kenya’s economy if supported by media and policy makers alike.”

A 2011 article, by Peter Mutai for China’s Xinhua news agency, shows another narrative is possible. It manages to overturn much of the prevailing one in just its opening sentence:

“As hunger spreads among more than 12 million people in the Horn of Africa, a new study finds that investments aimed at increasing the mobility of livestock herders, a way of life often viewed as “backward” despite being the most economical and productive use of Kenya’s drylands, could be the key to averting future food crises in arid lands.”

Mobility is the key that pastoralists use to unlock the scattered riches of Kenya’s drylands. The landscape may appear barren, extreme and risky to city-based journalists but the pastoralists have the knowledge and skills to take advantage of the land’s variability and diversity.

The old proverb that says “a fool looks for dung where a cow has never grazed” can perhaps be turned on its head to serve as a reminder of the riches – of stories and more – that a reporter can find if they follow the herd.

[This post was first published on the IIED blog]